In September 2020, this column on “Wheels of Courage” was published on JAPAN Forward.

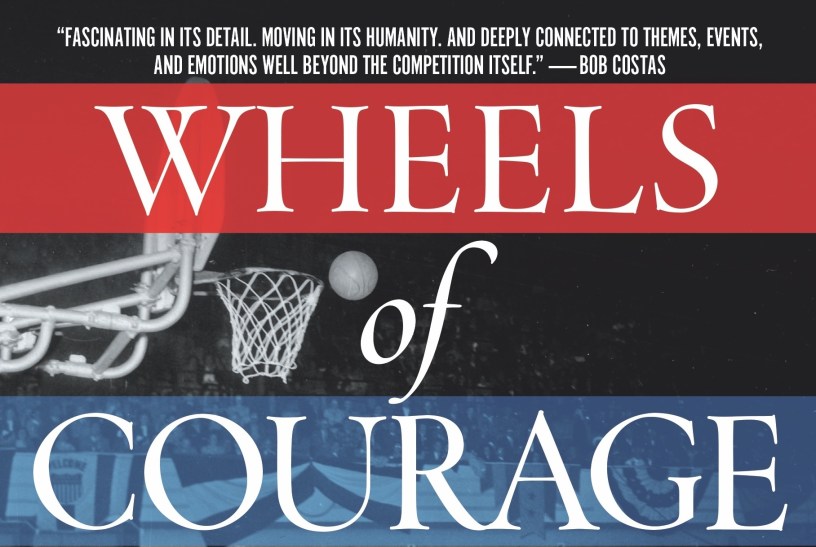

[ODDS and EVENS] New book ‘Wheels of Courage’ Explores History of Wheelchair Basketball and Paralympics

By Ed Odeven

In an expansive undertaking, author David Davis investigates the history and evolution of the Paralympic Games through the prism of wheelchair basketball.

His new book, “Wheels of Courage: How Paralyzed Veterans from World War II Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation,” tells the story of the wounded World War II veterans who were determined not to be defined solely by the labels and limitations that society placed on them.

“History has forgotten about the pioneering wheelchair athletes: the paralyzed veterans from World War II, both here and in England,” Davis told JAPAN Forward’s ODDS and EVENS in a recent interview.

“These men showed the world that people with disabilities could play a healthy and exciting brand of sports, and along with their innovative doctors and caretakers they helped advance the cause of rehabilitative medicine.

“Their efforts opened the gymnasium door to other individuals with disabilities, including women and youth, as well as those with other disabilities beyond paraplegia. Finally, through the Paralyzed Veterans of America, they were among the first individuals to lobby for disability rights for all individuals.”

From the aftermath of the Second World War to the final decade of the 20th century, Davis’ book, which was published in late August, illuminates the progress that was made.

It connects the past and the present, as well as the United States and Japan. Davis’ voluminous research effectively spells it out in his 400-page tome.

He points out how American expatriate Justin Dart Jr., a former polo patient and Tupperware Japan president, was a central figure in the struggle for societal acceptance for people with disabilities. What’s more, Dart witnessed the athletes’ courage and spirited competition at the 1964 Tokyo Paralympics.

Davis picks up the story from here: “He [Dart] was so impressed by the athletes that he hired a U.S. Paralympian to move to Japan with his wife and coach Tupperware Japan’s wheelchair basketball team.”

Nice gesture, indeed.

But why was it so significant in Dart’s life?

“The experience pushed Dart to become an advocate for those with disabilities,” Davis related. “When he returned to the U.S., he became one of the most important figures in the fight for the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. In fact, when President George H. W. Bush signed the ADA at the White House, next to him was none other than Justin Dart Jr. And for that you can thank the 1964 Tokyo Paralympics.”

Wheels of Courage author David Davis. (Credit: Robert Levins)

The Central Premise of ‘Wheels of Courage’

In explaining the project, Davis, who was born and raised in New York City before relocating to Los Angeles in the 1980s, summed it up this way:

“World War II veterans were the first group of paraplegics to survive their spinal-cord injuries, thanks to medical advances (sulfa drugs and penicillin) and the care of innovative doctors and physical therapists here and in England.

“These veterans invented wheelchair basketball and took the sport on the road, including a memorable contest in Madison Square Garden in 1948. Along with their comrades in England, led by the indomitable Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, they helped invent the Paralympics. And, through the Paralyzed Veterans of America, they were among the first people to lobby for disability rights for veterans and civilians.

“I tell this long-forgotten saga, yet another legacy of the Greatest Generation, through the words of the veterans and their doctors and caregivers.”

Two unidentified teams compete in a wheelchair basketball game outside Yoyogi National Gymnasium during the 1964 Tokyo Paralympic Games. (Credit: Australian Paralympic Committee / CC BY-SA 3.0)

While preparing to read this book, I wanted to know a bit more about how it materialized, so I fired off an email to Davis.

In his thoughtful response, he explained why he devoted countless hours to a subject that very few people know anything about, a project that consumed four years of his life.

“When I was doing research for ‘Waterman,’ [a biography of Hawaiian surfer and Olympic swimming medalist Duke Kahanamoku], I ran across a reference to the Rolling Devils wheelchair basketball team from World War II,” Davis told ODDS and EVENS.

“Turns out, they were all paralyzed veterans from WWII who rehabbed at a Naval Hospital in Southern California and were one of the very first wheelchair basketball teams in existence. That piqued my interest in the topic, and I took the proverbial ‘deep dive’ into the origins of sport for people with disabilities.”

Dr. Ludwig Guttmann in an undated photo. (CC-BY 4.0)

The Establishment of the Paralympics

Guttmann, a Jewish doctor, fled Nazi Germany in 1939 and settled in Britain, where his pioneering work planted the seeds for the Paralympics.

Five years after his arrival in the U.K., Guttman was appointed the head of the National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Aylesbury, England, where injured servicemen were treated. Guttman advocated “the use of compulsory sport and physical activities as a form of rehabilitation, integration, and motivation,” Paralympic.org reported.

As a result, wheelchair basketball, archery and netball became activities that he organized for physical rehabilitation for paralyzed veterans.

This trio of sports, Davis told WGVUnews.org in a September interview, “helped build up their chest, arm and shoulder muscles, which are vital for those who have lost the use of their legs.”

One hospital’s activities doesn’t produce a globally recognized quadrennial event on its own, but Guttmann’s vision began with the activities for his patients at the National Spinal Injuries Centre.

“He linked the Paralympics and the Olympics from the very beginning,” Davis stated.

“He organized the first Stoke Mandeville Games (the precursor to the Paralympics) on the very day as the opening ceremony of the 1948 London Olympics. And, in his speeches and his writing and in the trappings that he created around the Paralympics, he constantly linked the two.”

Continue reading the full column on JAPAN Forward.